Do You Dare Enter the House of Dior?

- Andrew Groves

- Oct 8, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 12, 2025

Power, Control, and the Horror Behind the Gilded Doors

Last week’s Dior show opened on an off note — or more precisely, three. The soundtrack of a specially commissioned Adam Curtis film began to play, its low piano tones reverberating through the space. Projected onto the giant inverted pyramid, they hung like a warning, signalling that something beneath Dior’s polished surface was already starting to come apart.

It was an unsettling beginning, in sound and in intent. The dissonance primed the audience for unease before a single image appeared, hinting that what followed would disturb, rather than flatter, Dior’s polished world. Curtis’s film would unravel the house’s mythology instead of celebrating it.

Then the title appeared: “DO YOU DARE TO ENTER THE HOUSE OF DIOR.” A door slowly opened into an eerily abandoned mansion, followed by a rapid succession of doors slamming shut on their own.

The Return of the Dead

Slowly, the ghosts of the house began to emerge. First came an apparition, Empress Elisabeth of Austria, stepping from a horse-drawn carriage in Galliano’s A/W 2004 couture show — a spectral imperial fantasy rolling into the salon. Ethel Cain’s A House in Nebraska began to play, a song of empty homes and grief that shifted Dior’s “house” from Parisian grandeur to American Gothic ruin.

Then Gianfranco Ferré, Christian Dior, and Maria Grazia Chiuri appeared — but the discordant notes returned, threaded through horror-film flashes and images of models gazing into mirrors: some reflecting different faces, others shattering as a voice asked, “Who are you?” The mirrors no longer promised stability but instead exposed the certainty of disappearance. Curtis held them up to Dior and showed the house not gleaming, but fracturing.

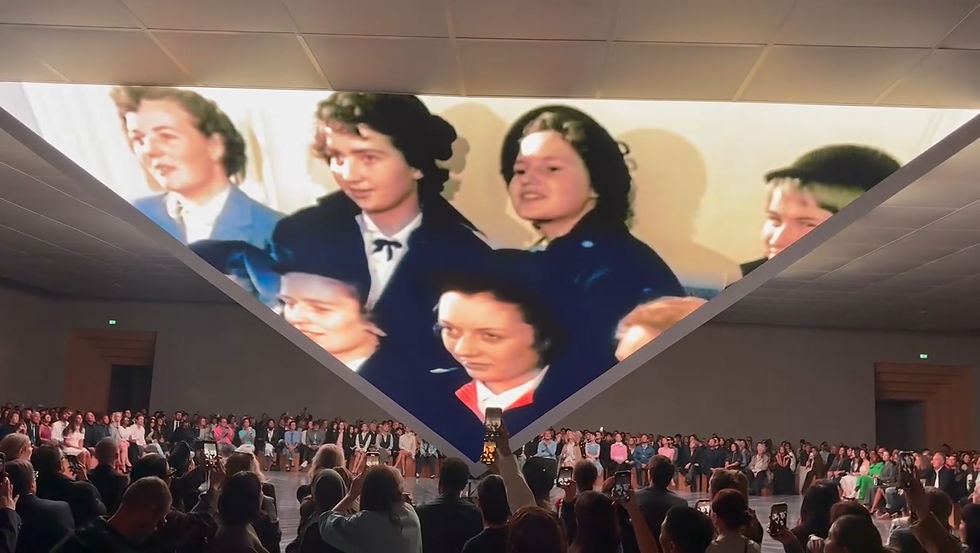

Black-and-white footage of a 1950s Dior audience followed, the screen mirroring the spectators watching below. The gesture recalled McQueen’s Voss (2001), where attendees were forced to confront their own reflections. Here, though, the reflection was temporal; fashion’s usual promise of the future turned inward, showing the audience not what’s next but what’s inevitable: their own disappearance, spectators destined to be folded back into Dior’s house of ghosts.

Then the house’s most troublesome ghost, Galliano, appeared — taking his bow in a full space suit: the couturier as astronaut, stepping out of heritage into absurd rupture. Dior’s legacy emerged not as stable history but as a theatrical myth, endlessly restaged, each revival another haunting of the house.

Control, Beauty, Doom

As archival footage of endless Dior shows played, Curtis cut in scenes from horror films — Michael Myers pulling on his mask in Halloween, a child screaming — while the runway shows continued, indifferent. The montage turned the ritual of dressing into something darker: the model and the murderer performing the same act of transformation. Identity slipped away, replaced by mask and spectacle. Glamour and horror blurred, each revealing the other’s dependence on repetition, detachment, and control. The next cut exposed who held that control, shifting from performance to possession.

Curtis cut to the 1996 Met Gala: Princess Diana in a shimmering Galliano-for-Dior slip dress, the first outing of his reign. Beside her, Bernard Arnault, the owner who had just installed him, the man who held the house and controlled it all. Then came a jump to Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950), a story of guilt and disguise centred on a bloodied dress kept as evidence. Off-screen, Marlene Dietrich had demanded that all her costumes be made by Dior, tying the film’s fiction of incrimination back to the brand itself. Curtis let a line play from Stage Fright’s villain: “So long as I have the dress, I’m the one who decides how long the show will run.” The splice was brutal, Arnault as the man with the dress, Diana as the one compelled to perform in it: control, beauty, and doom in a single cut.

As the line ended, Curtis flung us into chaos: the frenzy of a fashion audience jostling to get into a show, bodies knocked to the ground, a shrill voice wailing. Couture appeared not as refinement but hysteria. Then Lana Del Rey’s Born to Die kicked in; glamour already edged with fatalism, now became inseparable from death.

As the crowd’s disorder mounted, Curtis cut to Norman Bates in Psycho, frenzied, emerging dressed as his mother and wielding a knife toward the screen. Bates’s disguise is pure Gothic: a figure compelled to inhabit and revive the dead through dress, with the family home transformed into a crypt that will not release its hold. In that light, Dior’s darker truth surfaced— the house that refuses to die, compelling each new designer to revive its ghosts through dress.

Back Into the Box

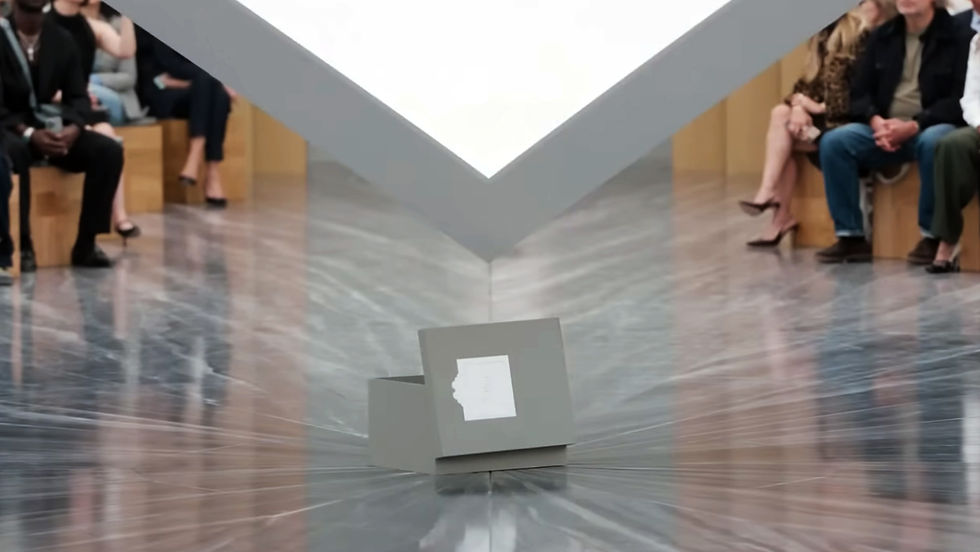

Then the film began to run backwards. Time itself reversed: Dior’s 1950s models retracing their steps, gestures erasing themselves as if history were being unwound. The montage quickened, images folding in on one another, until every ghost of Dior was pulled down into a single grey shoebox placed beneath the inverted pyramid. It was a horror-film gesture, the container as reliquary and coffin. Everything — the spectacle, the hysteria, the hauntings — collapsed inside a plain grey box in the middle of the room.

The Reckoning

Back in June, I argued that Anderson’s Dior menswear debut cast the house in religious terms. Dior, I wrote, was rooted in Catholic ideals: order, symmetry, sanctity. Couture as moral architecture, every seam an act of discipline and devotion. Anderson, raised amid Northern Ireland’s sectarian divides, revealed how Dior’s perfectionist Catholic edifice could be unsettled by Protestant ambiguity.

Three months on, for womenswear, he shifted register. This time, the critique came via Curtis, a filmmaker who specialises in unmasking the ghosts of power. By commissioning Curtis, Anderson forced the house to acknowledge its ghosts in public. The film was less a prelude than an exorcism: Dior confronting what it cannot bury, its splendour revealed as ruin. In Curtis’s reading, Dior has ceased to be a cathedral of couture and become a haunted house; a Gothic ruin of mirrors and collapsing histories, where beauty survives only as haunting.

And, like any good horror story, there is no release. The question that opened the film still hangs in the air: Do you dare enter the house of Dior?

Comments