The Wrong People in the Right Clothes

- Andrew Groves

- Oct 16, 2025

- 4 min read

Yesterday, CNN asked what happens when extremists wear fashion brands, using Stone Island as its example of how symbols can become contested. The question sounds simple, but it reveals something deeper — how easily fashion absolves itself from the hierarchies it helped create. It assumes brands are neutral until corrupted by bad actors. But fashion isn’t passive. It has always been one of the clearest ways societies express power, class, and control. And when those symbols slip into the wrong hands, it’s not corruption; it’s exposure.

From Officers to Outsiders

The story begins long before Stone Island. For over a century, brands like Burberry dressed the officer class, not the ranks. Officers were permitted to buy their own uniforms from military tailors, garments that signalled social status as much as rank. Ordinary soldiers were not allowed to do the same; their clothing was issued, not chosen. That difference, between permission and obligation, reinforced a hierarchy that ran from the battlefield into civilian life.

By the 1980s, that same hierarchy began to unravel. On the football terraces, early casuals started wearing Burberry — not to imitate privilege but to invert it. The gabardine coats and checked scarves that once defined the officer class became tools of working-class performance and defiance. What had been a sign of authority was recast as a symbol of mobility, a way to claim access to worlds that had systematically excluded them.

For the brands, that shift was deeply unsettling. When refinement crossed class lines, it exposed how fragile those hierarchies were. Burberry’s later attempts to distance itself from so-called “chav culture”, scaling back its check and rebuilding its image, were less about aesthetics than control. It wasn’t extremism being policed but class.

The Politics of the Terraces

In Britain, the link between class and visibility runs deep. The terraces of the 1980s and 1990s became arenas of self-presentation, where working-class men performed status under constant scrutiny. Groups such as West Ham’s ICF, Birmingham’s Zulu Warriors, and Leicester’s Baby Squad used designer clothing to claim identity and territory.

These spaces were never uniform. During the 1970s and 1980s, the far right and the National Front were active on the terraces, using them as recruitment grounds. Yet on the same terraces stood Black and Asian lads, figures such as Cass Pennant, Barrington Patterson, and Riaz Khan, prominent members of football firms who used clothing to assert visibility within environments that often excluded them. On the terraces, race, class, and masculinity could be negotiated through dress rather than dictated from above. Clothing became both camouflage and declaration, a way to move through a policed world on one’s own terms.

The Rise of the Badge

It’s no coincidence that Stone Island’s founder, Massimo Osti, drew on military uniforms, garments shaped by systems of rank and control, reimagining them through material innovation rather than ideology. A lifelong communist, he understood the semiotic power of uniform and quietly subverted it through design.

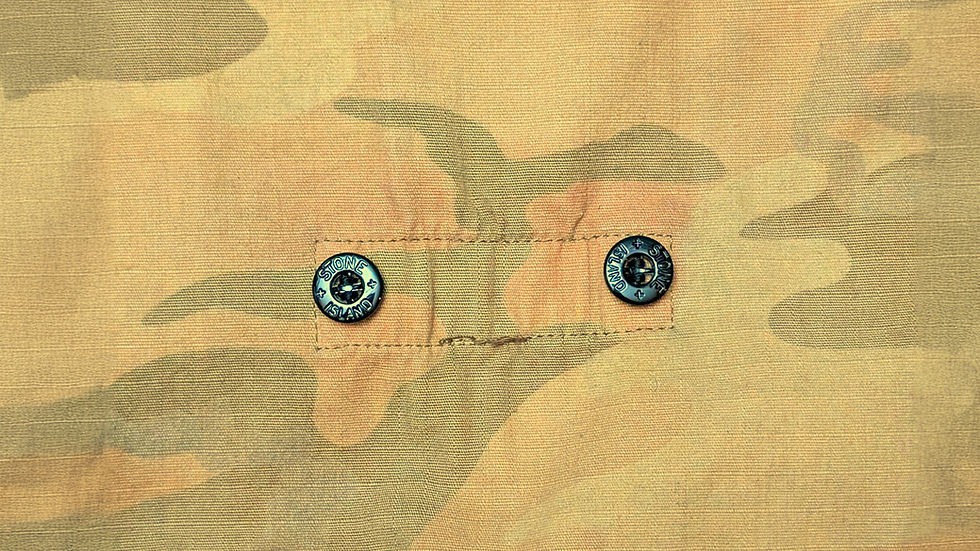

It was in this environment that Stone Island became increasingly visible on the terraces in the early 1990s. From the outset, its detachable badge carried more meaning than the garments themselves. In the early 2000s, many casuals removed the badge to avoid being singled out by police; today, a younger generation insists on “getting the badge in.” That reversal shows how the patch became a focal point of visibility, alternately hidden or displayed depending on context. Over three decades, it has been read and misread, signalling belonging, aspiration, or suspicion, its weight always tied to how visibility is policed.

Class, Costume, and Contamination

When commentators present Stone Island’s visibility among far-right figures as a matter of unwanted association, they miss that the wider language of exclusivity, utility, and discipline that runs through menswear has always been designed to signal power. The difference lies in who wears it.

Both Tommy Robinson and Keir Starmer have been seen in Stone Island. Each provokes deeply divisive reactions in Britain, yet the responses to how they wear the brand could not be more different. Robinson, from the working-class ranks, is read as contamination — his choice damns not just him but a whole class. Starmer, from the officer class, is read as costume — an awkward performance that mocked him but left the brand untouched. Both are political performances, but only one triggers moral panic. The dividing line isn’t ideology; it’s class.

Control and Meaning

Commentators often claim that brands “lose control” of their meaning, as if it were ever theirs to begin with. Meaning moves through wearers, through the policing of bodies and spaces. The Stone Island badge, the Burberry check, the Fred Perry laurel: each is shorthand for authority and belonging. They can be hidden, displayed, or repurposed, but never made neutral.

The issue isn’t that extremists sometimes wear designer clothes. It’s that fashion keeps reproducing the same masculine hierarchies that make extremity legible, symbols of discipline, unity, and power that promise belonging while policing who belongs. Fashion built those codes; it didn’t lose them. Until menswear as a whole recognises that, it will keep being shocked when the wrong people wear the right clothes.

Comments